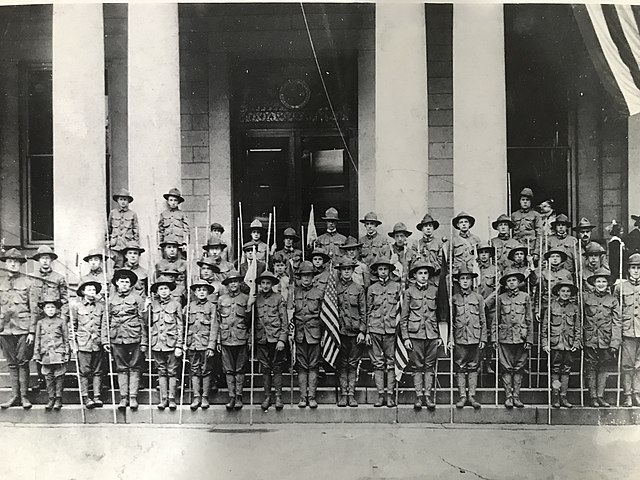

A Boy Scout Troop from the early 20th century. Photo from Wiki Commons.

Earlier this month, the Boy Scouts of America announced a major change: it would change its name to “Scouting America.” Gone would be the traditional focus on boys and young men. “We are an organization for all,” BSA president Roger Krone declared. “It’s time our name reflects that.”[1]

I admit I was surprised. But I shouldn’t have been. After all, the recent history of the Boy Scouts has been a history of policy evolutions toward maximal inclusion. In 2015, the Scouts opened their doors to openly gay leaders[2] (despite, in 2000, successfully securing from the Supreme Court the right to regulate their own membership).[3] In 2017, transgender youth became eligible to join.[4] And in 2018, the main Scouting program was opened to girls and young women, and rebranded as “Scouts BSA.”[5]

As momentous as they may have been, though, those changes always struck me as incremental—as if, in their own way, they were building up toward something. This latest transformation seems final, like the once-and-for-all shutting of a book. The rupture with the past is now complete. And something about this rupture feels like a rupture in my own life story.

I was an Eagle Scout—or, better, I am an Eagle Scout. Over the years, my family poured endless hours of investment into the Scouts, at the pack and troop and national levels. No other program—except maybe competitive speech and debate—more directly formed my teenage social imaginary.

I no longer recognize the organization that has now emerged from its ideological chrysalis. In adopting a theoretically infinite scope and clientele, the organization has now finally rejected what it was originally for: preparing boys, in all their wildness and particularities, for virtuous manhood.

* * *

It would probably go too far to say that “Natural Law” has always been fundamental to Scouting. But at the heart of the Boy Scout movement was something very like it. The guiding premise of the organization, in both its value statements and its practices, was the intuition that nature is an ordered cosmos, a world of moral and physical limits which should be respected.[6]

Begin with the simplest point of all: the moniker Boy Scouts. The very name reflects that there are such things as boys, and their welfare is worth consciously pursuing. What’s more, their welfare is worth pursuing in the context of a single-sex program, because such spaces promote boys’ growth and flourishing in a unique way.

To be blunt, boys behave differently when girls are around. As Mary Harrington rightly points out, “the vast majority of members of both sexes are heterosexual, meaning the probability of sexual interactions—consensual or otherwise—will escalate considerably in a co-ed setting.”[7] In this context, “sexual interactions” should be defined loosely: I always appreciated that I could take risks, and make mistakes, in an environment where I wouldn’t be shamed in front of a crush. This principle holds even if units are formally bifurcated by sex. There are such things as camporees and jamborees, after all, which mix together a huge variety of Scouting units.

Furthermore, the nature of the Scouting program was decidedly “boy-friendly.” As Harrington notes, “human males tend towards social patterns in which they cooperate with peers and compete with out-groups”[8] So it’s no coincidence that competition dominated all the outdoor events I can remember, from pioneering contests to orienteering races to games of Capture the Flag. Where Scouting programming and advancement requirements are conceived as gender-neutral, that pedagogy will inevitably change.

To be clear, none of this is to suggest that Scouting should be sexist: long before the recent changes, BSA operated a coed Venturing program, offering many of the same outdoor opportunities to young men and women alike. But Venturing’s existence didn’t change the fact that the organization’s core commitment, as reflected in its flagship program, was the well-being of boys in particular.

Biological sex certainly wasn’t the only hard-edged limit that BSA demanded its members confront. There’s an old slogan that “Scouting” is three-quarters “outing,” and my experience certainly reflected that. Every month, we’d pack our backpacks and head out for a weekend of canoeing, or rock climbing, or—a perennial favorite—“wilderness survival,” where we’d construct shelters from trees and branches and try to last the night.

Crucially, these are all activities in which one’s own physical and mental limits come squarely into view. Stone and water and forest are powerful and primordial forces. They are not kind to unprepared or reckless boys. If your shelter fails, you’re sleeping in the cold. If your food burns, you’re choking it down or going hungry. If your food isn’t secured, you risk raccoons or bears.

If social media and smartphones teach young people that the world is evanescent and malleable, these outdoor activities teach the opposite. You cannot log out from the wilderness once you’re in it. You cannot block or delete the friend sleeping beside you. You cannot magically “level up” if you haven’t done the physical conditioning necessary to perform under stress.

One of the hardest chapters of my Scouting experience that I can recall was earning my “Athlete” activity badge, when I was a Webelos Scout (a transition point between Cub Scouting and Boy Scouting). I was a bookish, out-of-shape nine-year-old. I didn’t like being pulled away from my big stack of library books or Lego shelves. For the first time, I was forced to confront something I could not outthink: my own physical weakness.

At the time (circa 1999/2000), the requirements for the Athlete badge read as follows:

Do two pull-ups on a bar.

Do eight pushups from the ground or floor.

Do a standing long jump of at least 5 feet.

Do a vertical jump and reach of at least 9 inches.

Do a 50-yard dash in 8.2 seconds or less.

Do a 600-yd run (or walk) in 2 minutes 45 seconds or less.[9]

Note something important about these standards. They are markers of objective merit. (I vaguely recall that the associated language was something like “the Boy Scouts of America has physical fitness guidelines for young men.”). “Just give it a try” was not acceptable; the relevant benchmark was what can reasonably be expected of a physically fit young man. To earn the badge, I had to change my lifestyle. I had to learn to exercise.

In my case, it took a while for the exercise habit to take, but it finally did. To date, I haven’t missed a day of running in nearly twelve years. No change in my life has been more consequential. I lost 40 pounds, performed better academically, and drastically improved my relationships. That journey began with my Athlete activity badge training, whether I realized it or not. I didn’t need to be affirmed in my current state, or offered the possibility of marginal improvement. I needed to be called to objective excellence.

A few years later, this set of requirements was watered down to the following: “Do as many as you can of the following and record your results. Show improvement in all of the activities after 30 days.”[10] To be clear, this change wasn’t a concession to genuinely disabled Scouts, for whom accommodations were always available. It was a relaxation of the standard. And something crucial was lost in the process: the idea that you might need to change, to be better than you were, in order to meet the world’s objective demands.

But objective excellence, of course, goes only so far. Any talk of human limits, in the end, runs up against the ultimate limit—one’s own finitude before the Creator. As the Scout Oath insists, God and country are those basic realities to which the Scout is first obligated.

To be sure, BSA’s understanding of the divine was always theologically thin. The governing “Declaration of Religious Principle” states that “[t]he recognition of God as the ruling and leading power in the universe and the grateful acknowledgment of His favors and blessings are necessary to the best type of citizenship and are wholesome precepts in the education of the growing members,” but stresses that BSA “is absolutely nonsectarian in its attitude toward that religious training.”[11] I recall a number of cringeworthy interfaith worship services based on a mashup of Indigenous, Christian, Jewish, Muslim, and Baha’i texts, in keeping with that syncretic mood.

But this criticism should not be overdrawn. There is, after all, both an ecumenism of pastiche and an ecumenism of recognition. The former elides difference and commingles traditions; the second simply acknowledges the common spiritual reality “in whom we live and move and have our being.”[12] Before this Source, all human souls stand limited and imperfect.

This basic intuition, I would venture, underpins a distinctly masculine sort of piety. Neither theoretically abstruse nor emotionally florid, this spirituality grasps the world in its radical givenness and its beauty, its utter dependence upon its Maker. It is a religious mood perfectly captured by the common prayer of Camp Constantin in Texas, where I attended summer camp multiple years running:

For blue skies and blue waters,

For the wind in our sails

And the ground that we walk on,

For Scouts past and present,

And the food we are about to receive,

We thank thee, O Lord.

Amen.[13]

Of course this is theologically underdetermined. That is the point. As a unifying center for Scouts across confessions, it reflects precisely what Joseph Bottum has described as “the social unity in theological difference that characterized the old Mainline.”[14] And I would venture that it is an orientation that captures how a great number of men, past and present, think and speak of God. There is value in this. And it is hard to capture elsewhere.

* * *

I invoke the Protestant mainline deliberately. My feelings about the Scouts are akin to how, I would imagine, theological conservatives born and raised in mainline denominations feel about the deracination of their churches. The cradle Episcopalian does not wish to cease being an Episcopalian, simply because his leadership has let him down. It is the tradition in which he was baptized, confirmed, married, and in which his fathers were buried. He cannot abandon that tradition without abandoning a part of himself, losing or disavowing the continuity that has oriented his life.

For me, Scouting is the tradition in which I became a man. I cannot imagine what it would take for me to disavow it altogether, to see my Eagle award as a badge of shame or stupidity. I cannot severe those emotional ties. I will probably always, at some level, take the “Eagle Scout” title seriously. Perhaps this is my own weakness talking.

I’m well aware that new small-s scouting groups—like new denominations—are emerging to fill the void resulting from BSA’s decline. Of these new groups, the explicitly Christian organization Trail Life USA particularly stands out. My childhood troop dissolved under BSA and rechartered under Trail Life, and the organization clearly has a lot going for it. But as with all projects of breakaway and recreation, something vital is inevitably lost in the process.

Consider, for instance, the Trail Life oath, which is explicitly modeled after the Scout Oath:

On my honor,

I will do my best

To serve God and my country;

To respect authority;

To be a good steward of creation;

And to treat others as I want to be treated.[15]

Of course, the substance of all this is beyond cavil. But compare it to the old Scout Oath:

On my honor,

I will do my best

To do my duty to God and my country;

To obey the Scout Law

To help other people at all times;

And to keep myself physically strong, mentally awake, and morally straight.

There is a thunderous, time-out-of-mind rhythm to the old words. Duty to God and my country has a martial energy. Obey the Scout Law churns with the force of the Decalogue. And the clattering cadence of physically strong, mentally awake, and morally straight bores forever into the mind. By comparison, the Trail Life oath feels rather like the rhetorical equivalent of Hunt’s ketchup: good and inoffensive, but lacking the punch of the original.

To be clear, I don’t say this as a criticism of Trail Life. It isn’t their fault that the organization became necessary. I mention it only to stress that traditions are not easily created. The old initiation ceremonies by which boys became men were meaningful because they stood outside of time: they were inherited, mythic, beyond the historical process. One did not create new rites, but repeated them.[16]

Perhaps, decades from now, the BSA will be a distant memory and the Trail Life alternative will carry the force of the old Scouting creed. But that time is not yet here. And in the meantime, I mourn for what’s been lost.

* * *

Eighteen years after earning my Eagle rank, I now have two sons of my own. I always imagined that, one day, I would do Scouting with them as my father did with me. I imagined hosting their crossing-over ceremonies from Cub to Boy Scouts, and pinning on their own Eagle medals.

Those days will not arrive. They will not arrive because the Scouting movement to which I gave so much (and from which I received so much) can no longer see my sons, in their boyhood, as individuals worthy of special interest. I do not want them to be seen as desexed achievers, checking an “Eagle” box for college-admissions purposes. I want them to be men of virtue.

The time has undoubtedly come to build something new. The leaders of Trail Life are correct about that. And when the time comes, my sons will probably join. Trail Life rightly recognizes nature and the limits it imposes, even if the BSA has forgotten them.

But I am still sad. I am sad my boys will not participate in the tradition of Baden-Powell and the Lone Scout and Philmont Scout Range and Florida Sea Base and the Boundary Waters and whittling around a campfire and lighting branches with Sterno and eating horrible granola bars and mucking out latrines and sleeping under the stars with the Order of the Arrow and wearing the uniforms and memorizing the Scout Law and so much else.

That is the legacy I carry with me. I always will. A Scout is loyal.

[1] Debbie Elliott, “After Years of Scandal, Boy Scouts of America Changes Its Name to Scouting America,” NPR (May 7. 2024).

[2] Michelle Boorstein, “Boy Scouts of America Votes to End Controversial Ban on Openly-Gay Scout Leaders,” Washington Post (July 27, 2015).

[3] See Boy Scouts of Am. v. Dale, 530 U.S. 640, 641 (2000) (“The Boy Scouts asserts that homosexual conduct is inconsistent with the values embodied in the Scout Oath and Law, particularly those represented by the terms ‘morally straight’ and ‘clean,’ and that the organization does not want to promote homosexual conduct as a legitimate form of behavior.”).

[4] Katie Zezima, “Boy Scouts of America Will Allow Transgender Children to Join,” Washington Post (Jan. 30, 2017).

[5] Mike De Socio, “Boy Scouts Pitch a More Welcoming Tent at Their National Jamboree,” Washington Post (July 27, 2023).

[6] John Courtney Murray’s account of the “public consensus,” as essentially rooted in natural law, is germane here. See John Courtney Murray, We Hold These Truths; Catholic Reflections on the American Proposition (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2005), 115 (“Only the theory of natural law, I said, can give an account of the moral experience which is the public consensus, and thus lift it from the level of sheer experience to the higher level of intelligibility toward which, I take, the mind of man aspires.”).

[7] Mary Harrington, Feminism Against Progress (Washington, D.C.: Regnery, 2023), ebook ed.

[8] Harrington, Feminism Against Progress, ebook ed.

[10] Boy Scouts of America, Webelos Handbook (2003), 124.

[11] Boy Scouts of America, “Declaration of Religious Principle,” Charter and Bylaws of the Boy Scouts of America (2019).

[12] Acts 17:28.

[13] Camp Constantin, “Camp Grace,” Boy Scouts of America: Circle Ten Council (accessed May 8, 2024), https://circleten.org/posts/29098/camp-constantin.

[14] Joseph Bottum, An Anxious Age: The Post-Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of America (New York: Image, 2014), ebook ed.

[15] Trail Life, “Who We Are,” Trail Life USA (accessed May 8, 2024), https://www.traillifeusa.com/distinctives.

[16] Cf. David D. Gilmore, Manhood in the Making: Cultural Concepts of Masculinity (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1990), 124–25 (“Many traditional societies are highly structured in the way they acknowledge adulthood for both sexes, providing rigid chronological watersheds as, for example, ceremonies or investments, complete with magical incantations and sacred paraphernalia.”).