Editor’s Note: National Review has granted Anchoring Truths permission to reprint a 2023 review by Prof. Joel Alicea of Mere Natural Law by JWI Founder & Co-Director Hadley Arkes, along with Prof. Arkes’s response to Prof. Alicea. Please find Prof. Arkes’s response below, originally titled in National Review as “The Nature of the Law.”

How can I complain of Joel Alicea? I’ve known him for a long while, and he is characteristically cordial, even gracious — as he credits my writing, and my charm — in his review (“Anchoring Originalism,” July 10) of my book Mere Natural Law. I think, though, that he gave the readers a serious misreading of the book, and I hope that my own corrective will be received in turn in a cordial way.

Alicea touches the main line of my argument in the book — before he takes a deft turn and leads the reader away from the center of the argument. Quoting me, he aptly says that I take as “the very ground of Natural Law” and “the principles that govern our judgments in Natural Law” those precepts of common sense that can be grasped by ordinary folk. Alexander Hamilton caught the core of the matter in Federalist No. 31, where he wrote of those “primary truths, or first principles, upon which all subsequent reasoning must depend.” These are things to be grasped per se nota, as true in themselves. One of the things grasped in that way is the “law of contradiction,” that two contradictory propositions cannot both be true. And what is grasped in the same way, by ordinary men, is the axiom that was taken by Immanuel Kant, Thomas Reid, and Thomas Aquinas as the first principle of all moral and legal judgment: that it makes no sense to cast moral judgments of praise or blame on people for acts they were powerless to effect.

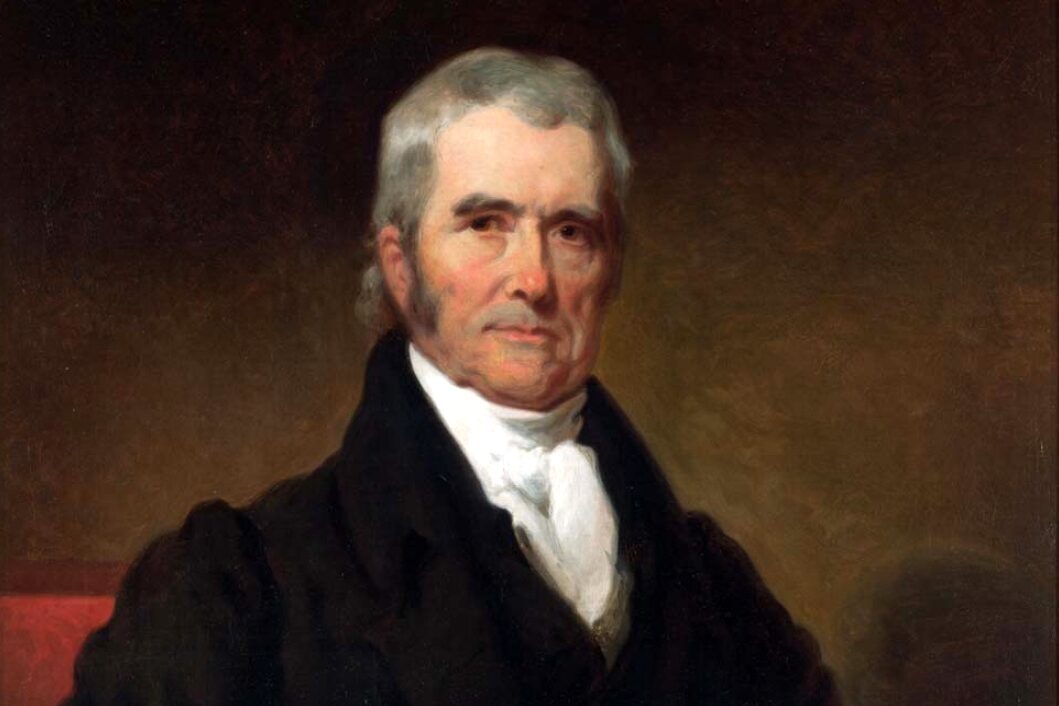

That axiom not only underlies the insanity defense; it may explain finally the deep wrong in principle of racial discrimination. More than that, the implications springing from this axiom run widely through our laws. James Wilson and John Marshall followed Hamilton in recognizing axioms of this kind as those “primary” truths that form the ground of our law. The critical point here is that these are not theories. It’s not a theory that we may not hold people responsible for acts they were powerless to effect, any more than it’s a theory that two contradictory propositions both cannot be true. What Alicea seems to miss is that a system of law drawn from axioms of this kind cannot be merely a theory of natural law, but the real thing.

But that is the point, so critical to my argument, that Alicea deliberately steered around, and we ought to be clear on what was at stake for him here. No one, he says, “denies that judges rely on principles of reason in adjudicating cases; the controversy is over whether judges must or should apply substantive moral principles not otherwise contained in or adverted to by the positive law.” “Arkes,” he goes on to say, “conflates principles of reason with principles of morality.” And yes, that is exactly the point. What he apparently doesn’t see is that those axioms of reason do in fact supply the principles of our practical judgment on the substantive issues that persistently arise in our law. Combined with others, they come to bear in a practical way on such matters as withholding medical care from a child born with spina bifida, or compelling a businessman to take on a public function of funding contraceptives and abortifacients for his employees. Aristotle saw that the most distinctive mark of human nature was the capacity to give reasons over matters of right and wrong. And so why should it come as a surprise that the axioms of reason would indeed supply the ground for our reasoned judgment over matters of right and wrong? As Kant understood, the “laws of freedom” were nothing less than those “laws of reason” that rightly claimed to govern our judgments in the domain of freedom, where people were free to form the paths of their own acts.

Once that point is in place, it would hardly stand as a “disorder” in our constitutional lives if judges needed to appeal back to those axioms of reason as they tried to frame their judgments in the most coherent way. But Alicea finds it “widely acknowledged by scholars that the Constitution, as originally understood, did not empower federal judges to set aside positive law in light of the natural law.” If so, that would have come as news to Wilson and Marshall, who quite notably moved beyond the text of the Constitution in reaching their judgments. Do we want to talk about cases? Surely there would be no more dramatic example under this head than the opinion of Marshall in that classic case of Fletcher v. Peck (1810).

There was a rescission by the legislature of Georgia of a grant in land, tainted by scandal. But the rescission affected innocent buyers of the land, and so when the case came to the Supreme Court, it plainly seemed to be a law “impairing the obligation” of a contract, coming under Article I, Section 10 (the contracts clause). But instead of deciding the case in that way, Marshall did something far more elegant: He showed that the contracts clause could be drawn deductively, through a syllogism, from that deeper principle on ex post facto laws, laws that made something punishable even before it was forbidden in the law. On that ground, Marshall could offer an argument quite striking: Georgia, he said, was a great state, part of the American union. But even if Georgia had been a separate sovereign state, outside the union, outside the Constitution, and outside Article I, Section 10, that law would still have been wrong. For its wrongness was rooted in a principle that did not depend at all for its validity on being mentioned anywhere in the text of the Constitution.

Alicea surely knows that I made the critical point in this book that judges do not have the sole and exclusive authority to protect natural rights. As the Declaration of Independence made clear, the defense of “natural rights” formed the purpose or telos of the whole government, of the executive and legislative no less than the judicial. And if Alicea knew my other writings, he would know that I’ve long taken the Lincolnian position on the authority of the political branches to counter and narrow the holding in any case, confining it to the two litigants.

My pitch, then, is that, at times, the judges must reach out to the plainest truths that are engaged in the case, even though they are not contained in the text, and do it simply for the coherence of their judgments. Alicea mentions the Dobbs decision on abortion, and let us take that as a second case in point.

In Dobbs, it was not a matter of inadvertence: The Court deliberately withheld premises that are vital to the pro-life argument. It deliberately held back from recognizing the human standing of offspring in the womb. The dissenters in Dobbs actually caught this point: They said that “the majority takes pride in not expressing a view ‘about the status of the fetus,’” and that “the state interest in protecting fetal life plays no part in the majority’s analysis” (emphasis added).

That sense of things was embarrassingly brought out in Justice Kavanaugh’s concurrence when he noted that “many pro-life advocates forcefully argue that a fetus is a human life” (emphasis again added) — “forcefully argue” as though there were no long-settled empirical truth on this matter, found in all of the textbooks of embryology. In other words, in this mode of conservative jurisprudence, the judges must affect not to know the plainest objective truth that bears on the practical judgment here, namely, that a fetus is a human being. And yes, Professor Alicea, that is exactly why I say that a conservative jurisprudence, shaped and truncated in this way, is a “morally empty jurisprudence.” No arty words, earnestly offered, can pretty that up.

Alicea seems to think that it would fall properly to someone else, not in judicial office, to incorporate in his judgment the truth that Kavanaugh somehow thought beyond his authority to speak. And yet that is precisely what would have been put into play if the Court had simply recognized that inescapable truth about the nascent being in the womb. It would have set the ground for the Congress to act under the 14th Amendment when the protections of life are being withdrawn from a whole class of small human beings. Instead, states were invited to consult the “value judgments” of their voters on whether they thought infants in the womb were really human and worth protecting.

Alicea seems to suggest that it would disfigure our Constitution, and rupture civic peace, if judges thought themselves free to recognize that key truth central to the substance of this issue of abortion. But here, to take a line from Henry James, Alicea may be making of himself a “victim of perplexities from which a single spark of direct perception would have saved him.” That direct perception could simply be focused on the exquisite brief the lawyers from Texas put before the Court in Roe v. Wade. They drew on the most updated findings in embryology to offer to the court these critical points: that the offspring in the womb has never been anything other than human from its very first moments, and that it receives nourishment from its mother but has never been merely a part of the mother’s body. That kind of case offered as compelling a ground as the Court has ever heard to reach that simple and familiar judgment: that the legislature had an ample justification in this flexing of its powers to legislate — in this case, to cast the protections of its law on a whole class of small, innocent human beings. Surely there was nothing wrenchingly unfamiliar in the Court’s acting in that way, nothing that should trigger our sense of courts running amok with “raw judicial power.”

But past all the lights and shadows, it is still not clear as to why originalism would offer a better defense of popular sovereignty than the moral ground of the natural law on the right of a people to govern itself. Alicea says that I don’t have a firm understanding of originalism. But what is his own understanding, drawn from his long law-review article “The Moral Authority of Original Meaning”? Alicea owned that he was not “arguing that originalism is our law,” but that it was “an implication of our positive law.” He also confessed that his “limited purpose was to show that a natural law understanding of political authority requires originalism in some form in the context of the American regime” (emphasis added). But this is to say no more than that originalism must involve a “basic law,” or constitution, telling us how laws are made and who has the rightful authority to make them. At the same time, Alicea fully recognizes that the sovereign people may change that constitution at any time. And he has also noted that the natural law does not entail any particular form of a constitution based on “the consent of the governed.” Why, then, should we suppose that it would entail this truncated, positivist form of originalism, with its immanent aversion to recognizing any principles of right and wrong outside the text?

What it all may come down to in the end is simply that telling line in the Declaration of Independence on “the Right of the People to alter or to abolish . . . and to institute new Government,” on grounds that “seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.” But the one thing, of course, that is never open to change is: that Right of the People to determine the terms of their own governance. There, in its simplicity, is the irreducible font of our constitutional order. Nothing in it entails, or makes necessary, what we’ve come to know as originalism; and nothing in originalism conveys the fullness, the moral depth of its rightness.