Conservative jurisprudence has a long and unfortunate lacuna. Ironically, this gap involves an issue lying at the heart of American conservative political philosophy: state power. Whatever the shortcomings of Common Good Originalism (I count myself among the skeptics), Law & Liberty’s recent exchange between Holden Tanner, Josh Hammer, and Jesse Merriam brings to light a legal framework to re-empower the exercise the plenary police power of states and for this reason deserves serious attention. This consideration is, although not perhaps the intention of these writers, much needed and a better use of Common Good Originalism than constitutional interpretation.

It may seem surprising to say that originalism ignores state power. Originalist jurists do consider the issue occasionally, but such regard usually concerns federal courts’ limitations rather than developing states’ authority per se. I argue this ignorance emerges from several factors that simultaneously enable rich federal constitutionalism while concealing the depth of the states’ police powers: the robust nature of the federal constitutional debate and the Constitution’s historical contingency; the delegation of the federal government’s powers, which makes those powers simpler and more easily theorized than the states’ broader authority; and the fact that state courts follow federal jurisprudence, aping its theories and therefore passing below interpretive notice themselves. The last is particularly lamentable. Since the powers of state and federal governments differ greatly under the Constitution, theories applying to one ill-fit the other.

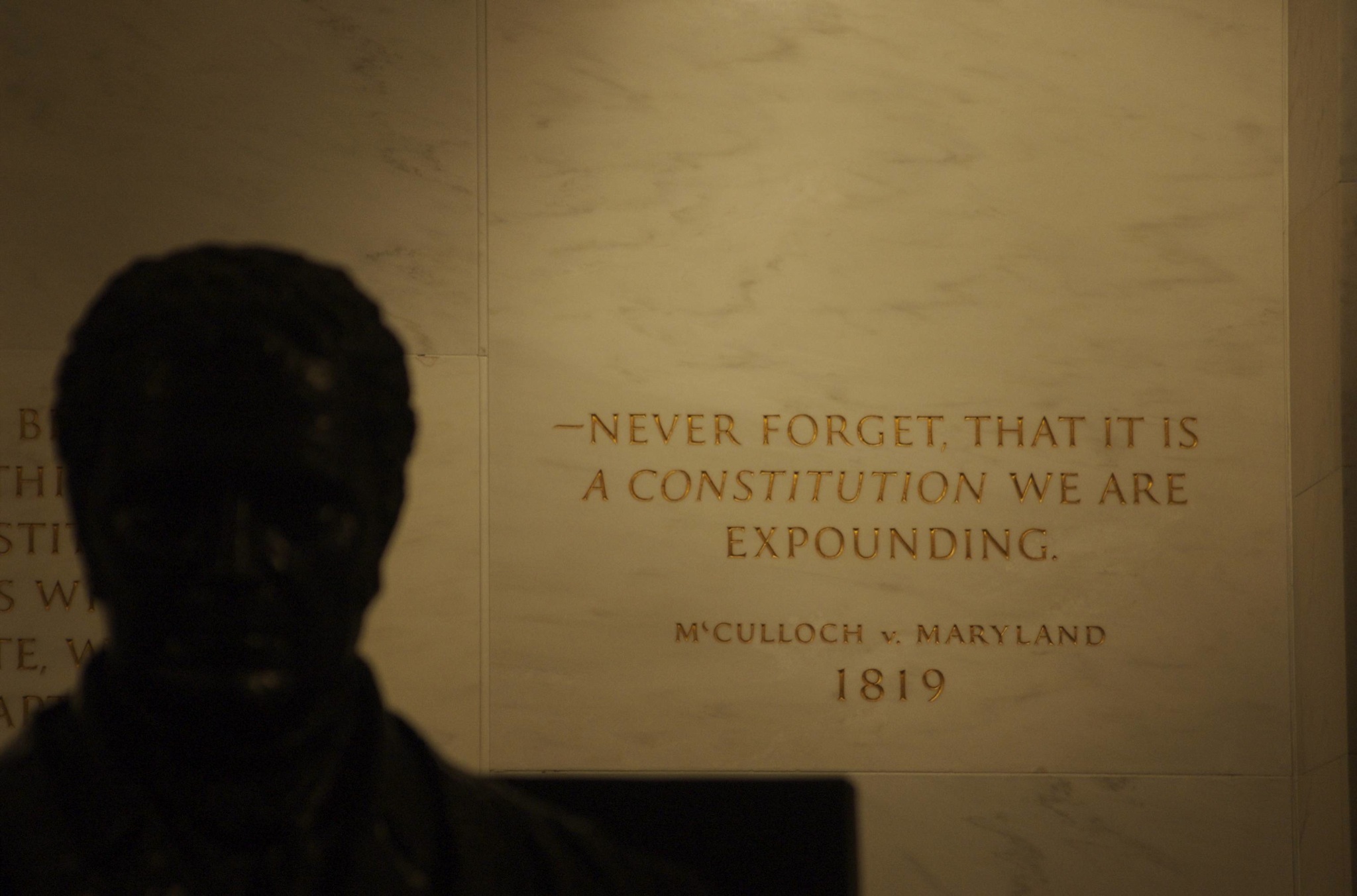

While it emerged early in constitutional interpretation that “the intention of the instrument must prevail” and “that this intention must be collected from its words,” this basic element of originalism is neither revolutionary nor unique to the United States. All countries with a written code follow a similar maxim with civilian codes going to an even greater extreme of textual rigor. What makes originalism unique, and uniquely applicable to the US Constitution, is the rich historical context of its ratification. While other law codes, such as Germany’s Civil Code (the Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch), had a complex development, these codes don’t view themselves as the products of history (instead seeing themselves enumerating timeless principles). Therefore, they don’t vest the contexts of their origination with interpretive importance. This difference holds with common law where the general process of development matters less for interpretation than the facts of any individual case despite having an even longer development.

The federal constitution is different. It possesses a long, publicly debated development with an initial awareness that it emerged from a contingent process, meaning that the historical conditions producing it were important to its creation and interpretation. The ratification debates therefore matter to any interpretation (“we are all originalists now”). Philosophical differences chiefly emerge in how judges employ them to reach varying conclusions (even the most progressive justices cite the debates). These debates, moreover, couldn’t have reached their level of importance and excellence, being seminal in the history of Euro-American political thought, without widespread popular involvement. This context created a large, rich body from which to derive opinion and argument.

The debate’s contingency, richness, and awareness that it encumbered the Constitution, provide it unique interpretive relevancy. State constitutions lack this development. They typically emerge from indefinite historical contexts through stereotyped conventions with little to no public engagement or via popularly ratified amendments involving political campaigns lacking sustained debate, depriving them of the fodder necessary for originalist rumination.

Our federal system’s structure and the Constitution’s role in it also make originalism fit state governments poorly. Even if sufficient documents and debate exist to provide grist for the originalist mill, states have powers unconstrained by constitutional mandate. While their constitutions limit and guide their exercise, state governments, especially courts, must consider matters absent from constitutional texts, especially at common law. While federal courts must punt such issues, state courts can’t. Instead, they must rule using available resources. In such contexts, textually-focused originalist theories provide an inadequate guide for proper constraint and exercise of legal authority since originalist frameworks can’t consider powers outside the original document.

The final problem of state-oriented originalism emerges hence. Contemporary originalism developed against progressive jurisprudence to constrain the federal judiciary to its delegated powers. It never theorized plenary powers. While state bodies could have initiated such inquiries on their own, two factors limited them: first, the problem that originalism is a theory of written law while states exercise many uncodified powers; and second, state courts often move in lockstep with federal courts, sometimes even constitutionally substituting the jurisprudence of federal courts for their own. Consequently, even when state courts adopt originalism, they pin themselves into theories that are ill-suited to their peculiar legal context and prevent themselves from developing specific theories for their own powers. This ligature stunts conservative state legal theory since states’ plenary power has a distinct moral centering that federal powers lack (as even Scalia recognized in his dissent in Lawrence v. Texas).

The Common Good Originalists rank among the first to realize originalism’s misfit to states. Messrs. Tanner and Merriam have called state courts central to the project, though for Mr. Tanner, at least, this seems to be a strategic rather than theoretical position. In truth, state courts aren’t essential only for Common Good Originalism. State courts are primary for any legal movement because of the overwhelming number of cases they hear and the state courts’ authority under Erie v. Tompkins to bind the decisions of many cases that federal courts do hear. If originalism has failed to achieve interpretive dominance among states that it enjoys with federal courts, its indeterminacy results from providing weak jurisprudence to these courts and applying top-down influence ill-suited to American federalism. Common Good Originalism, given its emphasis on sources of law outside the strictly positive (i.e. statutory and constitutional) provides a robust framework upon which to build a theoretical conservative jurisprudence guiding the exercise of plenary powers.

If originalism only weakly reigns in state courts, people don’t seem to notice. The American people tacitly align the two together. Abortion exemplifies this elision. Few people realize that the originalist position isn’t pro-life. It is instead agnostic, leaving prohibition or permission up to the states. Despite this fact, in both the popular and even professional imagination, Roe’s overturning necessarily means abortion bans. This elision isn’t a coincidence since most of Roe’s opponents also oppose abortion. Lumping the issues together ipso facto is a fallacy, however. This fallacy is easy to accept when one considers that Roe has almost no pro-choice opponents. We should find this fact surprising since opposing Roe isn’t more pro-life than pro-choice. That pro-life/pro-choice and pro-Roe/anti-Roe coincide so neatly shows how far federal judicial action substitutes for state-level politics: the question is no longer political but moral, no longer federal but state.

Conservatives’ long ignoring state court-level jurisprudence is the major reason for this elision. Because conservatives, the party most interested in state power, spent so long pushing a theory of law lacking arguments about plenary powers, conservative jurisprudence has functionally removed states from action. This lack of reasoning has allowed the progressive narrative of domineering federal jurisprudence to run roughshod over states. While these progressives are most responsible for federal usurpations, the conservative failure to check this invasion left states with no theoretical apparatus to fight back. Worse, the embrace of a federally-centered theory like originalism tacitly endorsed the substitution by making the federal constitution the center of conservative legal argument with the states as mere afterthoughts to be shoe-horned later. Erie seems to chain the federal system to the states very effectively, providing a unique leverage point to shape definitively the growth of American jurisprudence by planting seeds at this fundamental level.

Enter Common Good Originalism. While the intellectual framework of Common Good Originalism contains serious flaws, especially at the federal level, it provides potential to unhobble state systems from federal binding. Since state courts aren’t constrained by delegation, they’re free to use moral reasoning, natural law, economic considerations, or any other guide. This fact leaves the field wide-open for creative solutions to legal problems, which Common Good Originalism should enable if pursued properly.

The major obstacle to reform is the chain forcing states to follow federal precedent, an entanglement that constitutes state-imposed reverse Erie. Perhaps this entanglement explains Mr. Hammer’s implicit belief that Common Good Originalism should focus on federal courts. Even so, it’s unclear why he and his fellow travelers concentrate so intently on overturning Erie. It’s doubtful that an Erie-free system would be any friendlier to Common Good Originalism. Moreover, the Erie Doctrine, far from restraining state courts, as Mr. Tanner asserts, empowers them. Under Erie, the current situation of state courts is lions cowering before the mouse. They should focus on putting the roar back into the whimper.

Understanding the history of Swift and Erie clarifies this point. Swift was Justice Story’s effort to extend federal courts’ jurisprudential authority, completing the centralization of American jurisprudence that he himself began in Hunter’s Lessee. Story reasoned that by centralizing common law, federal courts could create a system far excelling states in efficiency (at least in commercial cases). This system’s superiority would lure those subject to diversity jurisdiction while exercising moral suasion over those who didn’t. The system failed. It transcended the original bounds Story envisioned and created a patchwork of jurisprudence that encouraged forum shopping. Brandeis ended this coup in Erie by restoring state supremacy over issues of general common law. Messrs. Tanner and Hammer are wrong to assume there is no federal common law: as a practitioner of admiralty law, I assure them there’s robust federal common law in domains entrusted to the federal system by the Constitution. In admiralty, this includes common law topics like torts, bailment, and even unique forms of product liability. The issue, therefore, isn’t whether the federal system has common law but the extent of law subject to its grasp. Subtler understanding of the history of Swift discloses this problem.

Mr. Hammer’s reasons for lamenting this change aren’t clear. One suspects he believes that by reinstating Swift, federal courts could exercise the greater suasion envisioned by Story to force states to adopt Common Good Originalism. If so, he’s too clever by half (and may not understand Swift’s true scope). Not only is such domination unlikely (it would take decades of nearly sequential sympathetic administrations to affect this change via judicial replacement), it’s as likely to backfire since his opponents could use the same power against him.

Mr. Tanner joins the attack on Erie for clearer reasons: he believes Erie, far from empowering state courts, neuters them. This position is quizzical. Reading the Swift decision, it’s far from clear that Story took New York jurisprudence “on its own terms.” The opposite is true. Story argued that the requirement to apply state law in that circumstance didn’t extend to state common law, only to state “statutes,” whatever that meant, and that federal courts could create their own common law within certain domains, contravening state law.

Erie, far from wrenching common law reasoning from state courts, returned them to power. In Erie, the lower court ignored the two possibly relevant jurisdictions’ common law and, following Swift, applied the federal common law of tort, which arrived at a conclusion at variance with the states. Brandeis held this result gave the federal courts impermissible superiority vis-à-vis state courts, binding federal courts to state decisions.

Mr. Tanner asserts that in practice federal subservience doesn’t happen. But case law and common experience don’t confirm his assertion. Mr. Tanner argues that in practice courts use only the “judicial opinions” and not morality and local custom to derive their decisions. Setting aside the obvious problem of whether courts sitting in common law jurisdictions should ever ignore precedent (a.k.a. judicial opinions) in favor of the judge’s interpretation (what else could it be?) of morality and local custom, it isn’t true that federal courts run roughshod over state courts by taking their results literally but construing their process figuratively.

Federal courts are contrarily careful in construing state law. While they sometimes fail to refer to state courts’ reasoning in their own decisions, this usually only happens when the result is obvious, such as stating a claim’s elements. When the issue is at all unclear, federal courts regularly delve deeply into their state counterparts’ reasoning. When issues emerge with genuinely new points of state law and federal courts don’t abjure jurisdiction on that ground (another indication of federal acquiescence), federal courts carefully construct what state courts’ reasoning is likely to be. If too difficult, they regularly certify questions to state supreme courts. If state courts prove them wrong with later decisions, federal courts abandon their precedent to follow the state’s decision.

Contrary to Mr. Tanner’s assertions, Erie seems to chain the federal system to the states very effectively, providing a unique leverage point to shape definitively the growth of American jurisprudence by planting seeds at this fundamental level. Only contrary action by state governments themselves interfere in this relationship, necessitating if anything closer attention to the extra-judicial impact of state politics. In this domain, originalism has been as much foe as friend.

Perhaps Mr. Tanner’s position can be explained by his objection to “legal realism,” though his use of this term, which he employs interchangeably with “legal positivism” three paragraphs later, appears idiosyncratic, as does other James Wilson Institute alumni’s use. One assumes, as above, that he means judges don’t engage in deep, jurisprudential inquiry of the facts at hand but instead plumb idiosyncratic policy preferences (living constitutionalists) or chimerical historical and textual illusions (originalists) to make their decisions. This is an idiosyncratic use of the terms. Legal realism and legal positivism aren’t interchangeable in their common use. While both theories answer the question what is law, the first replies with the judicial process (i.e. the decisions of judges) and the second with the legislative process (i.e. the source of a rule). Not only are these theories different (Justice Scalia, for example, is a legal positivist but not a realist), they are inapposite to explain the issue at hand. The continued confusing use of these terms obscures important arguments.

This article was originally published at Law & Liberty and may be found here.