An appeal to conservatives for an originalism of moral substance, by Hadley Arkes, Joshua Hammer, Matthew Peterson, and Garrett Snedeker.

Conservatives have taken a certain pride in the doctrines of Originalism that have won their devotion over the last 30 years, and they have found a deep satisfaction in seeing some of their most accomplished young lawyers appointed to the bench over the last four. But in truth—in sobering truth—the theories that have been offered us in the name of “conservative jurisprudence” have been muddled for decades. And now those doctrines threaten to disarm conservative judges as we are about to plunge into the gravest crisis of the regime since the Civil War.

The Biden Administration plans to challenge the American constitutional order and initiate a radical regime change by means of both legislative force and sweeping executive orders. The aim of the Biden Administration and America’s tightening oligarchy is to bring forth a structural change in our form of government and our laws.

It hardly overstates the matter to say that a critical aim of the Left is to establish, in effect, a one-party state. They are steadily trying to teach that conservatives and Republicans are illegitimate and unrespectable; that conservatives should not be welcome in respectable circles; that the conservative voice should be barred from the media; that conservative books should be barred from advertisement. Even more seriously menacing, they now argue that the powers of corporations should be engaged to bar conservatives from employment in law firms, corporations, and the media.

The animating objective of this new “order of things” is to establish, and to enforce ruthlessly, a scheme of “identity politics” in all branches of American life. The American people are to be broken into a series of tribes, set against each other by color, by race, by “sexual orientation.”

These measures will be countered in federal courts. Wherever they stand, and whether they wish to or not, the response of our federal judges will directly shape the course of the great civic conflict that is now heightening throughout our nation. That conflict is now at our judges’ doorsteps. American’s deepening divide is not going to subside anytime soon.

Thanks to the Trump Administration and a Republican Senate, the federal courts now include a number of judges celebrated by the Right for having a more serious perspective on jurisprudence than their peers. But just as “conservative jurisprudence” steps up to bat, it finds itself in its own serious crisis. The premises and perspective of Originalism are in question. We no longer have confidence that “Originalist” judges will rise to the challenge America now faces.

It took but one well-placed shock delivered by Neil Gorsuch, and many conservatives woke up to discover last June that the conservative legal movement had been rendered impotent long ago. They were only now awakening to the news. The failure of what usually passes as Originalism in theory has been clear to many of us for decades. With the placement of so many conservatives to the courts, however, it is now failing in practice—and news has broken out to a wider circle of Americans who had not been paying attention.

We stand together to oppose the timid, positivist “Originalism” currently on offer, which ignores both our broader Anglo-American tradition and the influence of natural law on our nation’s founding. We propose a new consensus in its place—a bolder, more robust jurisprudence rooted in the principles and practices of American constitutionalism before the last century of liberalism began its attempt to remake America. We are now in the midst of a crisis of a tottering regime, and we call on judges to act accordingly: as statesmen anchored in enduring principles, with skills of prudent judgment, not as technocrats focused entirely on the text, with no attention to the underlying principles that give meaning to that text.

What Bostock Revealed

There is no better example of the failure of originalist jurisprudence than the argument of Neil Gorsuch in the Bostock case on transgenderism. Senator Josh Hawley (R-Mo.) caught the sober truth of the matter when he declared, on the Senate floor, that this decision marked “the end of the conservative legal movement, or conservative legal project, as we know it.” If this method of interpretation is universally applied to what the courts will face in the coming years, as civic conflict escalates the American way of life we are working to preserve will simply cease to exist.

Justice Gorsuch had risen to the Court highly vetted for his command of Originalism and textualism. But his misstep in Bostock evinces the folly of a morally neutered, overtly positivist approach to interpreting legal texts. On the question of whether “sex” in the Title VII statutory text refers to biological sex or so-called subjective “gender identity,” there can be no escaping the stark moral choice that lies just below the “plain,” “dictionary” meaning of the word. The meaning of sex is grounded in the objective, enduring facts that must ever mark the difference between males and females. That meaning of sex will not be dislodged, and it’s the meaning that had to be decisive in these cases, regardless of what dictionaries said or left unsaid in 1964.

The travesty of Bostock revealed the pitfalls of a denuded jurisprudence that solely relies on proceduralist bromides. Those tag lines have pretended to a new preeminence over the timeless truths of the Anglo-American legal order. Today’s legal eagles exalt procedure over substance. They treat an adherence to their interpretive methodology as intrinsic victories, even though the Bostock decision threatens lasting damage in disfiguring our laws and even the lives of our families.

As the saying goes: one more “victory” of that kind, and we will be undone.

Originalism’s Original Sin

The romance of conservative jurisprudence faded over decades of incompetent selection and vetting by Republican presidential administrations and allied outside forces. But we must give credit where it is due: The initial decades of the modern Originalist project, encapsulated by Justice Antonin Scalia’s Supreme Court tenure, was successful in at least containing some of the rapid hegemonic rise and the sweeping reach of “Progress.” There have even been some substantial victories: Heller on self-defense, Citizens United on political speech, and a few others scattered here and there. And yet, more than those legal victories: With a political elite more and more inclined to take the gravest decisions in our law out of the hands of ordinary people and voters, Scalia, joined frequently by Justices Thomas and Alito, offered the main resistance.

We have even had some success in evangelism: “we are all originalists now,” Elena Kagan once averred. But was this a victory, or was it the illusion of a wide acceptance that would come, step by step, as Originalism and textualism were purged of their substance?

The supposed ascendance of Originalism has come along with the pablum of Bostock, the piffle of Regents of the University of California, and the sophistry of June Medical Services. And as decisions such as Obergefell and Bostock were celebrated by some as decisions quite compatible with Originalism, it became clear that Originalism as it is usually formulated has become a jurisprudence wholly wanting in moral substance. Worse, Originalism for many has become a jurisprudence that prides itself on its careful avoidance of addressing the moral substance of even the gravest cases. It has failed to transcend hollow positivism and now operates squarely within that flawed framework.

A landmark example of “conservative” positivist judging was provided by Justices William Rehnquist and Byron White, in their dissents in Roe v. Wade. These accomplished jurists paid no attention to the impressive brief written by the lawyers from Texas, which drew on evidence from embryology and principled reasoning to show why it was legitimate for the laws of Texas to protect those small, innocent human beings housed for a long moment in their mothers’ wombs. The dissents of the justices were focused rather on the decision to remove that question of abortion from the hands of voters, and the people, in the separate States. The designated “victims” were shifted from the babies killed in these surgeries, to the voters deprived of the chance to vote on this question.

This was exactly the line we heard in dissent in the cases on marriage: Our beloved Justice Scalia made the focus of his passion the fact that the defenders of marriage were deprived of “the peace that comes from a fair defeat” (U.S. v. Windsor). What he consciously and deliberately omitted from his dissents in Windsor and Obergefell was a substantive defense of marriage as it had been sustained in the laws: the legal commitment of one man and one woman. As he put it in his dissent in Obergefell, “it is not of special importance to me what the law says about marriage. It is of overwhelming importance, however, who it is that rules me. Today’s decree says that my Ruler, and the Ruler of 320 million Americans coast-to-coast, is a majority of the nine lawyers on the Supreme Court.”

This swerving from the central moral substance in these cases has not been a matter of inadvertence. It springs from something in the character of conservative jurisprudence, and it has been driven by the formula that 1) abortion and marriage are not mentioned in the text of the Constitution. And therefore 2) federal judges are not in a position to proclaim any “constitutional rights” on abortion or marriage that spring from the Constitution.

But “marriage” was not mentioned in the Constitution when the Court, in 1967, struck down the laws on marriage in Virginia that barred marriage across racial lines. Whether it is mentioned or not in the Constitution, the federal government had many reasons to deal with abortion, whether in the diplomatic and military posts abroad, in ships at sea, or in the District of Columbia. The mantra of “not in the Constitution” has become the readiest excuse for turning away from those hard judgments that turn out to be pivotal to any of these cases: the judgments on whether the statutes or the executive orders in question can finally be judged as justified or unjustified, defensible or wrongful.

“Textualism” is a detached and isolated literalism—it has been detached from those anchoring axioms and principles of law that supplied the ground of jurisprudence for the remarkable lawyers of the Founding generation: men like Alexander Hamilton, John Marshall, and James Wilson. This new jurisprudence is at loggerheads with the underlying principles and the moral ends that marked the jurisprudence of the founders.

This fixation on procedure ignores the fact that the whole project of the American Founding was directed to substantive ends. The “original” words at the origin, after all, told us that this government was founded for the purpose of forming a “more perfect Union”: to “establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our posterity.” As James Wilson famously said, our Constitution was not established to invent new rights, but to secure and enlarge those rights we already have by nature.

As Alexander Hamilton explained in Federalist #33, the power to do all things “necessary and proper” to the rightful ends of the government would be valid even if it were never set down in Article I, Section 8. For that passage reminds us of the claims that would be made for any decent person or government—that they would summon their just powers in the pursuit of good and rightful ends, claiming only the means that are legitimate and rightful. The ineffaceable understanding that there must be moral ends of the political order is the defining trait of any political order, and it must ever take an ascendance over “value neutrality.”

Some promote an ahistorical view of the founding generation as unduly “classically liberal” or individual liberty-obsessed. And yet, our common good-centric founding cannot, in any meaningful way, be construed as libertarian liberalism. At its best, the regnant legal order occasionally pays lip service to substantive conservative principles per se. At its worst, that order inadvertently aids and abets the toxic combination of economic globalization and cultural deregulation that characterizes today’s societal doldrums. As a similarly motivated statement put it two years ago, “The fetishizing of autonomy paradoxically [has] yielded the very tyranny that [legal] conservatives claim most to detest.”

Many friends and senior scholars have been working in this vineyard for years, offering the critique of conservative jurisprudence. All those interested in this debate should read, among other works, Harry Jaffa’s Storm Over the Constitution and Original Intent and the Framers of the Constitution, or the freely available “What Were the ‘Original Intentions’ of The Framers of the Constitution of the United States?” That critique has long made the case for a return to classic jurisprudence, more in tune with the founding, and that critique now shows signs of breaking through.

Now, we, the undersigned, call for a rejuvenated jurisprudential order based upon the following organizing principles of our own.

1. We hold that moral truth is inseparable from legal interpretation.

We believe that judges, like constitutional actors in the political branches, cannot—indeed, must not—avoid the moral and natural law implications of the questions that come before them. We believe that judges, in interpreting legal texts, can never be truly morally neutral on such rudimentary civilizational issues, no matter what they say or how they might delude themselves. The fact that our nation is sadly divided on these fundamental matters does not absolve judges from taking them into account. The pretense of neutrality on basic natural and moral truths is, in reality, an embrace of the jurisprudence of positivism. And positivism, in turn, often serves as a camouflage for more judgments that are hidden—and never tested in substantive argument.

Contrary to Justice Holmes, moral truth and jurisprudence are inextricably linked, and so the act of judging necessarily involves treating law as a teacher of our fellow citizens. To teach in a modest way, judges should embrace their role as a co-equal branch to articulate the first principles of moral and legal judgment. We only ask judges, as Ralph Lerner argued years ago, to show what duties individual actors in the constitutional order possess. We ask them to do their duty: to test the underlying moral justification for why a law exists and explain why republican government requires each actor in the constitutional order to do the same.

As Hamilton said in Federalist #78, judges hold a unique role within the separation of powers since their authority derives from the reasoning, or persuasiveness, behind their opinions. We attach more credence to their rulings as we plainly see their coherence. We call upon judges to be republican schoolmasters, as John Marshall was, teaching anew the first principles underlying our republican system of governance. If “conservative” judges fail to take on this role, their colleagues on the courts will continue to serve as schoolmasters of rival doctrines offering a new version of the will to power: a moral relativism brooking no limits, not even those objective truths in nature that distinguish men from women. As judges waive their moral responsibility, they surrender our governance to the rule of “experts” and the supremacy of the administrative state.

2. We hold that the Anglo-American legal order is inherently oriented toward human flourishing, justice, and the common good.

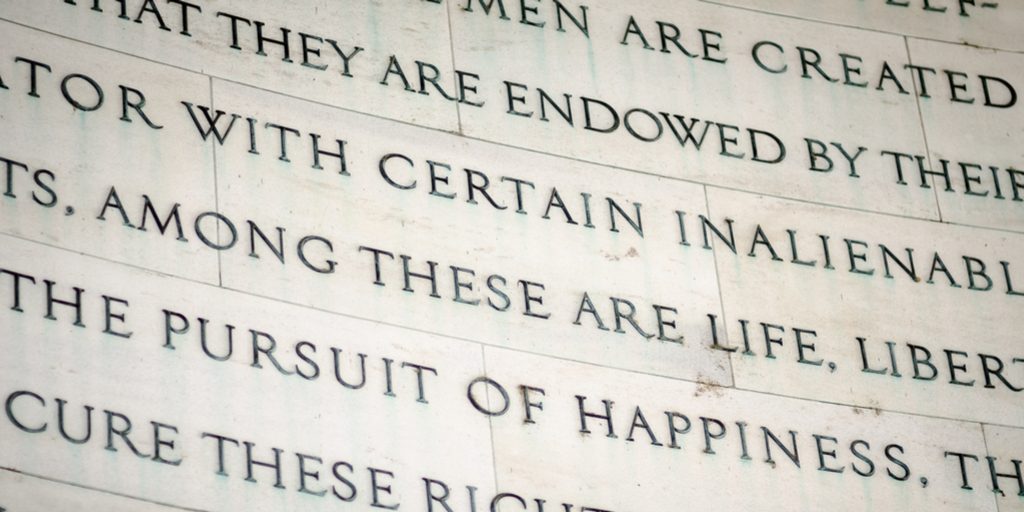

The Declaration of Independence, which announced the formation of the sovereign American people, rested its claim on certain self-evident truths about the rightful and wrongful governance of human beings. The founders appealed to “the Laws of Nature and Reason,” and to the Author of those Laws, “Nature’s God.” From that moral ground of our freedom and rights there arose a shared commitment to natural rights and attendant duties. In the Declaration’s appeal to justice, “just powers” of government are ordered toward both the “Safety and Happiness” of the whole people for whom law is “wholesome and necessary for the public good.”

The Constitution’s preamble enumerates substantive ends—the very reasons, the founders tell us, that their Constitution was adopted. They are, unanimously, ends that pertain to the commonweal of the nation, of communities, families, and individuals. They are not merely whatever ends happen to be adopted by the positive law.

Certain procedures to achieve those ends are necessary: these procedures are bound up with the purpose of fostering argument and reasoned deliberation, and securing the consent of the governed. Those procedures draw us into a discipline of reasoned judgment on the things rightful for a government to do. That discipline, deepened by the separation of powers, has offered a salutary restraint on the exercise of arbitrary power.

But our substantive concerns cannot be narrowed to the sole purpose of ensuring “fair” or “neutral” procedural rules, as though democracy is all procedure and no substance—as though we were free to choose genocide or slavery so long as we did it in a democratic way, with the vote of a majority. But neither can those ends be reduced to the purpose of maximizing individual liberty or individual autonomy, as though liberty and autonomy were simply good in themselves, regardless of the ends to which they were used.

The notion that the American Republic was created to maximize unbounded individual liberty or autonomy is an egregious, ahistorical anachronism. As the Virginia Declaration of Rights and countless other writings make clear, “no free government, or the blessings of liberty, can be preserved to any people but by a firm adherence to justice, moderation, temperance, frugality, and virtue and by frequent recurrence to fundamental principles.”

We believe in the “Originalism,” then, of Founding-era luminaries such as Alexander Hamilton, Chief Justice John Marshall, and Justice James Wilson: a jurisprudence with an anchoring moral ground, directed to naturally ordered, common good: this “Originalism” is our true Anglo-American inheritance. We believe these substantive ends ought to imbue constitutional interpretation, as we try to apply the clauses and to understand the telos, or purpose, for which those clauses have been formed. And this may be done, as well, within the confines of what some modern constitutional scholars call the “construction zone.”

3. We reject literalist legal interpretation and hold to the common-sense jurisprudence of the founders.

Conservatives often employ a “textualist” interpretive methodology that considers nothing but the plain—often acontextual—meaning of a given word or set of words. We believe this is misguided. Opposition to teleology and purposivism in legal interpretation has taken the form of trite condemnations of “legislative intent.” But the only rational way to interpret a legal text is both through its plain meaning and the meaning given to it by the distinct legislative body (or plebiscite) that ratified it. We would pay particular attention to the enunciated purpose(s) of the law and to the distinct societal function that such a law was devised for at the time of its enactment. Ratio legis, or the “reason of the law,” must inform and guide the plain meaning of the words on the page.

When the Congress, in 1964, sought to ban discriminations based on “sex” as well as race, it is entirely implausible that those words were ever understood at the time, by the Congress or anyone else, to bar the firing of people who earnestly professed to believe that they were not really of the sex into which they were born. True, a text may reveal, over time, implications that run beyond the understanding of those legislators who enacted the text. True, “legislative intent” is often not enough on its own to establish adequately the proper interpretation of the text—but this is no reason for judges to ignore the intended purpose of the law.

If “conservative” judges refuse to adopt the sound and traditional jurisprudence outlined above, they effectively cede this role to their peers on the Left. And those colleagues have demonstrated for decades, across the generations, that they have no problem in defining law in terms of moral purpose and the common good as they are pleased to define it. This is a form of tyranny that cannot be countered or tamed if conservatives disarm themselves and forego the discipline of moral reasoning that must ever be a part of judging.

If our friends claim that judges on the Left will take this as a new license for moral reasoning untethered, our answer is: why do we suppose that we cannot tell the difference between arguments that are plausible or specious? The answer to the Left is to show why their reasoning is false; it is not to end all moral reasoning and disarm conservative judges.

4. We believe in a jurisprudence that is, in the truest and most profound sense of the term, conservative, in preserving the moral ground of a classic jurisprudence.

Legal pedagogy and discourse, much like their political brethren, too often take the dichotomous form of Left-liberal versus Right-liberal. Legal Left-liberals, in obeisance to civil libertarianism and cultural progressivism, extol the virtues of Justice Louis Brandeis’ “right to privacy” and lionize the implicit intersectionality of Carolene Products, footnote four. Legal Right-liberals, in obeisance to economic neoliberalism and Randian conceptions of maximizing individual liberty, elevate the pursuit of limited government and its structural corollaries—federalism and the separation of powers—to the status of highest legal good.

We believe in the necessity and importance of federalism and the separation of powers to the American system but reject the notion that they compose the highest legal goods. Rather, we believe in a distinctly conservative approach to our legal order that prioritizes the health, safety, prosperity, and the flourishing of nation, communities, families, and individuals alike. It is a conservative jurisprudence worthy of a complementary conservative politics that is able, willing, and eager to exercise political power in the service of good political order—or justice in accord with nature and morality.

We begin then with a reverence for what was given to us by our own founders. We would conserve that inheritance at a time when it is being derided and vilified. When we recover the purposes and ground of our laws as they were understood by the founders, we will recover a jurisprudence that ought to earn the confidence of all thoughtful persons.

Perhaps “conservative” is no longer the right word to describe how such a political effort must operate at a time in which a corrupt, desiccated liberalism is the true “norm.” But this is a problem of semantics. The word now suffers from the fact that so-called conservatives have failed to conserve anything meaningful. A truly conservative jurisprudence and politics today that threatened actually to be effective in conserving good political order would say and do what its vicious opponents will no doubt describe as “radical,” “extremist,” and “fascist.” So be it. There are also words for those who fail to perform their duty to God and country for fear of the names their opponents call them.

Conclusion

We call for our fellow legal conservatives to recognize, soberly, the ruinous depths of our status quo and to join us in acting accordingly. We call our friends to break away from a jurisprudence that has underserved and underwhelmed—both practically and morally—and diminished our understanding of the proper ends of the law. We call our friends to something new by calling them again to something old—the teaching of the American Founders, as they understood the traditional Western principles of law and its interpretation. These principles existed before the Constitution was written. They are accessible to us now, and always will be.

This statement originally ran in The American Mind and is reprinted here with permission.