By Ataturksvg NevitNevit Dilmen Ataturksvg CC BY SA 30 httpscommonswikimediaorgwindexphpcurid=16060686

We’re at the first anniversary now of Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Center, when six conservative justices fulfilled the hopes nurtured over 50 years and finally overruled Roe v. Wade. I was as pleased as any of my friends to see the Court slay that Great White Whale. But I was working and writing in the pro-life movement, along with friends such as Michael Uhlmann and John Noonan, before Roe v. Wade. And even my friends on the Supreme Court will acknowledge that the Court did not accomplish, in Dobbs, what we had set out 50 years ago to accomplish.

It wasn’t a matter of inadvertence: the conservative majority deliberately withheld the premises that are vital to the pro-life movement in going forward now, in the States as well at the federal level, in acting through Congress. Most notably, the majority held back from recognizing the human standing of the child in the womb.

The dissenters in Dobbs caught the matter precisely: they said that “the majority takes pride in not expressing a view ‘about the status of the fetus’. . . .the state interest in protecting fetal life plays no part in the majority’s analysis.” [My italics]

The problem for the conservative judges was a theory about the rightful and wrongful reach of the judges, quite apart from the moral substance of the case. And that runs back to a mistake that was made by the conservative dissenters in Roe, a mistake that has governed “conservative jurisprudence” over the past 50 years.

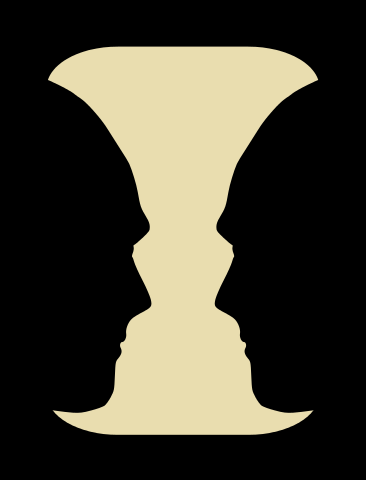

The psychologists used to show a drawing [Rorshach Test] that could be seen in two different ways. Some people, looking at the picture, would see a Lady in a Hat. Others would see a Vase. And it would not occur to either one that the picture revealed something different from what they noticed.

Fifty years ago the lawyers from Texas in Roe v. Wade composed an exquisite brief, drawing on the most updated findings of embryology and principled reason, and put these points before the Court: that the offspring in the womb has never been anything but human from its earliest moments, and never merely a part of its mother’s body.

The Court had before it an argument as clear and compelling as any argument the justices had ever seen, and they could have judged, as they’ve judged in the past, that the legislature of Texas had been amply justified in using its legislative power – in this instance to cast the protections of law on small, innocent human beings resident for a moment in their mothers’ wombs. To see the case in that way was to see the Lady in the Hat.

The majority in Roe, of course, did not see it that way. But the dissenters might well have seized upon it. They could have declared, as the mistake in the judgment, that the Court failed to sustain the laws in Texas protecting small, nascent beings.

Instead, the dissenters, Justices White and Rehnquist, fastened on the argument that would become a mantra for conservative jurisprudence: The text of the Constitution said nothing about a “right to abortion,” and therefore a federal judge was in a position to proclaim no such right arising from the Constitution.

And there the matter would be fixed down the years, through Dobbs: the conservatives never saw the Lady in the Hat, the choice of sustaining the laws in protecting unborn children. They saw only the Vase: that the villainy of the Court lay in flexing “raw judicial power,” inventing a new “right” never mentioned in the Constitution.

And that is why, when the Court finally overthrew Roe, many conservatives insisted that the work of the Court was done. Declaring that “right” to be no part of the Constitution was all that the conservative jurists had ever promised to do. But it would have made a profound difference if the Court had affirmed the human standing of the child in the womb.

The predicate would have been laid then for Congress to invoke the Fourteenth Amendment when the protections of human “life” were being withdrawn in the Blue States from a whole class of small human beings. And the States would have been enjoined then to consider how the killing of these small beings would be woven in with their other laws on homicide.

Instead, the States were invited to consult the “value judgments” of their voters on whether they thought infants in the womb were really “human” and worth protecting.

Roe not merely created a right to abortion; it changed the culture. It converted abortion from a thing to be abhorred, discouraged, and forbidden, into something approved, celebrated, and encouraged. The conservative justices in Dobbs did nothing to start undoing those moral lessons.

The redeeming part of the decision would be found in Justice Alito’s opinion for the majority. He managed to show that there was no principled ground for regarding the small being in the womb as anything less than human. But he held back from drawing the moral conclusion that sprang from that analysis. He would leave it to others to draw that moral conclusion, whether people in elective offices or perhaps conservative judges in the courts below.

A conservative judge, faced with a case of mifepristone or other chemical abortion, may observe that the chemical may be safe enough for the user but not for the victim, the one killed by the pill. To take that step would invite the Supreme Court to affirm that judgment and finally cross a critical line.

But conservative judges are cautious and likely to be unwilling to take that step.

And the Republican political class has ever been befuddled and uncomfortable in talking about abortion. The task may have to fall then to Alito himself to take that next step, for he may be the one person on the scene with the wit and the nerve to do it.

This piece originally appeared in The Catholic Thing and is being republished with permission.