“We Have no Right to Happiness.” So proclaimed the title of C.S. Lewis’s last essay written before his death in 1963. What he meant was that we have no moral right simply to take what we want to satisfy our desires, whatever those desires happen to be. That is an old recipe for a society in which the strong do what they will and the weak suffer as a result. Yet Lewis sharply distinguished the abuse of the principle from the real thing. The American Declaration of Independence, Lewis noted, insisted that all men had an equal right to pursue happiness within the bounds of the moral law, and this was because all men are equal before God and ought to be treated equally by the law. That remained an important political axiom in a century when fascists, Nazis, communists, and even some democrats, in nation after nation, were denying it.

As Americans, we are heirs to a political tradition founded on the idea that we are all created equal and endowed by our Creator with certain unalienable rights. That was a remarkable assertion in 1776, and it is one that Christians can celebrate and affirm alongside their fellow citizens without either abandoning historic Christian doctrine, on the one hand, or running the risk of affirming an untenable right to simply do what we want to do – whatever it happens to be.

But why would affirming this idea signal a departure from Christian doctrine? The answer depends on how we understand the God invoked by the Declaration of Independence and in subsequent American civil religion.

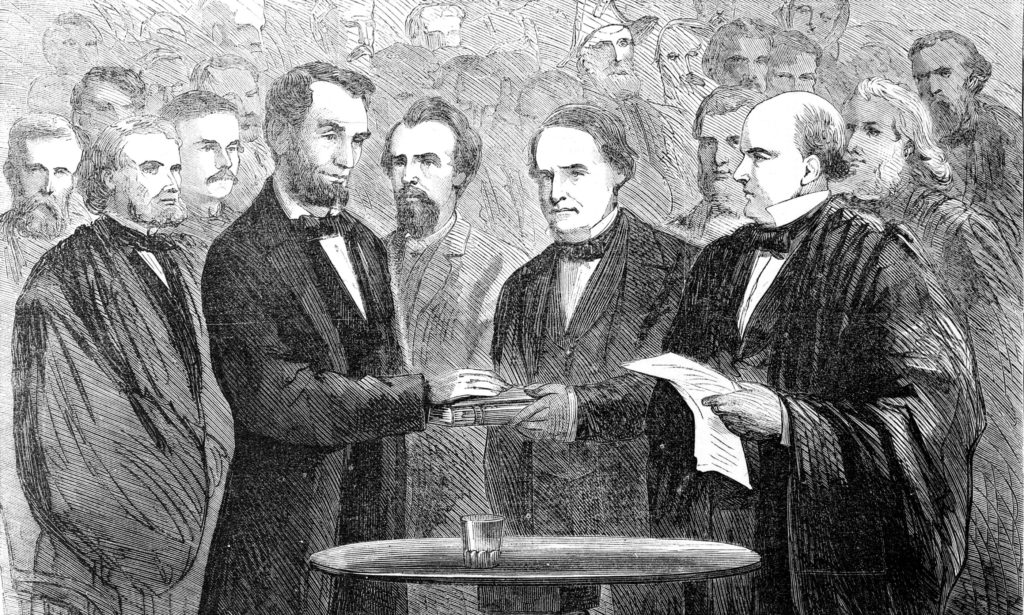

As one joke goes, an American student visiting Oxford University told her tour guide she had a hard time telling the difference between Lincoln College and Jesus College, each adjacent to the other. The tour guide replied, “Yes, most Americans do have a hard time distinguishing between Lincoln and Jesus.” Jokes tease on the truth, and the truth is that politics in America has a tendency to take on a religious quality. We remember Lincoln as a kind of civic martyr or secular saint. He dedicated his life to preserving the principles of the Declaration of Independence, and for that cause he was murdered on Good Friday in April 1865.

In his own life, Lincoln had preached that reverence for the laws should be our civil religion. The historian Pauline Maier wrote a famous book about the Declaration of Independence titled, simply, American Scripture, and the law professor Sanford Levinson’s book Constitutional Faith compares our debates about constitutional interpretation to debates about biblical exegesis and compares the Supreme Court to a civic version of the Catholic magisterium. Congress has long opened its sessions in prayer, the Supreme Court still begins with the plea “God save this honorable Court,” and, of course, inscribed on our money are the words “In God We Trust.”

In what God is it that we trust?

The 17th century French Christian philosopher and brilliant polymath Blaise Pascal began a poem, “God of Abraham, God of Isaac, God of Jacob / not of the philosophers and of the learned”

One of the fundamental questions about the American Founding–and this nation’s ongoing political project–is the precise character of America’s God. Was the God who was so often invoked in Founding era pamphlets and sermons and political documents the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, or instead the God of the philosophers and of the learned – a rationalized deity that was akin to nature itself or analogous to a clockmaker who designed the world and then let it run on its own accord? How we answer that question is relevant to how we think about American civil religion and what patriotism might look like for religious believers today.

In those first two paragraphs of the Declaration of Independence, the colonists invoked the God who authored the Laws of Nature and the Creator who endowed us with unalienable rights. In the final paragraph, they then appealed to the Supreme Judge of the world and proclaimed their reliance on the protection of divine Providence.

From one perspective, this all sounds very Christian, or at least Judeo-Christian: Nature’s God, the Creator, and a Supreme Judge who is Provident. Yet as C. Bradley Thompson writes in America’s Revolutionary Mind, summarizing a fairly common scholarly view, the “Declaration’s God is not the God of the Old Testament (nor is it even the God of the New Testament) but is Nature’s God.” Thompson here taps into the conventional scholarly wisdom that plays on Pascal’s formula: America’s God is the God of the philosophers and of the learned, not the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.

Ever since the ancient Athenians sentenced Socrates to death, many philosophers have been a little cagey with their arguments to avoid a similar fate. You have to read them carefully to see what they are trying to accomplish, and some scholars trained in that way of reading and thinking about philosophic texts view all of this talk of Nature and Nature’s God in the Founding as a departure from biblical religion. Sometimes they call the religion of the Founders deism, sometimes pantheism, and, occasionally, just atheism. The point is that philosophers who have written about God often have meant an impersonal first mover, or reason, or just nature itself – something different than the personal Logos of the biblical tradition – and the suggestion is that the Founders did the same.

The subtitle to Matthew Stewart’s recent book Nature’s God tells this story: The Heretical Origins of the American Republic. He puts it this way: “Although America’s revolutionary deists lavished many sincere expressions of adoration upon their deity, deism is in fact functionally indistinguishable from what we would now call ‘pantheism’; and pantheism is really just a pretty word for atheism.”

Some Christian scholars look at all of this and say: so much the worse for the American Founding. If it is all part of this Enlightenment project to water down Christianity, reduce God to Nature, and prioritize individuals and individual desires at the expense of what is good for our families and communities, then that is not inspiring news about the Founders or their political principles. If this is what liberalism is, and if American is liberal, then it is time to chart out a post-liberal future.

Patrick Deneen has offered the best-known example of this perspective. In his memorable phrase, “liberalism failed because it succeeded.” By liberalism, he means this whole Enlightenment era project of putting individuals and individual rights and individual will at the center of everything. Since he sees the American Founding as exemplifying that broader liberal project, he also draws a straight line from the Founding to the broken families, environmental destruction, economic excesses, and sexual confusion on display today.

Whether for celebration or lament, many scholars attribute to the Founding a modern and secular conception of Natural Law that is committed to pantheism and moral subjectivism and reduces all politics to will and power. Yet what we find when we look closely at founding era primary sources is a Natural Law tradition that is predominantly classical and Christian rather than modern and secular. Whether it is the pamphlet debates, private and public writings of prominent Founders, or moral philosophy lectures at the colonial colleges, nearly all relevant sources from the Founding affirm that natural law has a lawgiver who is understood as a creator separate and distinct from creation, and that reason grasps moral goods that are real rather than nominal or subjective.

Alexander Hamilton, like many of the Founders, associated the former constellation of ideas with Thomas Hobbes, and those Hobbist doctrines, Hamilton wrote, arose from a disbelief in “the existence of an intelligent superintending principle, who is the governor, and will be the final judge of the universe.” But “[g]ood and wise men, in all ages,” Hamilton asserted, “have embraced a very dissimilar theory” – one that derives natural rights from and roots natural obligation in the “eternal and immutable” Natural Law. James Wilson, in his famous lectures on law, similarly rooted the origins and authority of the Natural Law in God’s one paternal precept to “Let man pursue his happiness and perfection.” So were many of the Founders taught in the moral philosophy classes of the colonial colleges led by the likes of Samuel Johnson, Thomas Clapp, and John Witherspoon. This shared moral and theological framework gave shape to the Declaration of Independence and even to Thomas Jefferson’s original rough draft of that document, which proclaimed the “sacred and undeniable” truth that “all men are created equal” and that “from that equal creation” men derive “inalienable” natural rights.

One did not have to be a Christian to affirm these things, and some of the principal Founders such as Jefferson, Adams and Franklin, privately questioned the provenance of Hebrew and Christian Scripture and even mocked Christian doctrines such as the Trinity. Even so, Nature’s God looks a lot like what Christians from Augustine and Aquinas to Hooker and Calvin had long described as the Creator known to reason prior to any suprarational revelation that makes it possible to known him as Redeemer.

One pressing question for our pluralistic society is whether America’s God–the God often invoked in our founding documents and debates and still frequently in our public life today–stands in some sense as a rival to the God of Abraham and that God as understood by traditional Christianity.

Some of the Founders were Christians, some not so much, but nearly uniformly they believed God created the world and created nature, including human nature. They believed God exercised providence in human affairs, and one aspect of his providential care was in giving humanity natural knowledge of right and wrong. In short, they believed in a Natural Law and a natural lawgiver, something that Christians have long taught is presupposed by but not dependent on Christian revelation. This framework, rightly understood, allows religious pluralism to develop under a common affirmation of our natural rights, including the right to pursue happiness, without descending into the rule of the strong–something that is worth celebrating this Fourth of July.